I used to believe facts were currency.

If I put enough solid data on the table, I assumed the other person would eventually look at the pile, nod, and cash out their wrong opinion.

This belief lasted longer than it should have. About as long as I believed eating cereal for dinner was a phase, not a lifestyle choice I would later defend vigorously.

Here’s the uncomfortable reality:

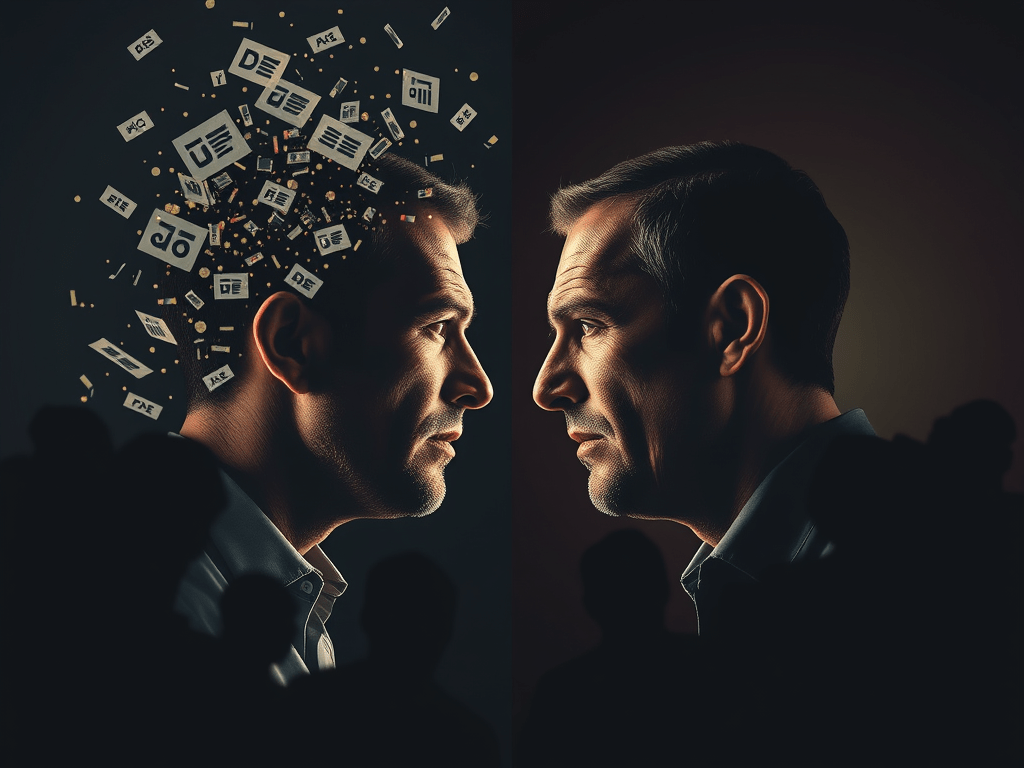

Facts don’t compete with other facts.

They compete with identity.

Most arguments fail not because the evidence is weak, but because the argument is aimed at the wrong target. We assume people are trying to be correct. Usually, they’re just trying to belong.

Beliefs aren’t opinions.

They’re uniforms.

When you challenge someone’s belief, you’re not disputing a fact. You’re challenging their tribe, their past decisions, and the role they’ve been playing for years.

That’s not a debate.

That’s a threat assessment.

This is why evidence loses to belonging.

Once something becomes tribal, truth becomes secondary. Agreeing with the “wrong” fact isn’t growth — it’s defection. And people don’t defect casually, especially not in public, and especially not online.

At that point, the argument is no longer about truth.

It’s a loyalty test.

This also explains why correcting people rarely works.

Correction doesn’t feel helpful. It feels like exposure. The brain doesn’t hear new information — it hears you’re in danger. Curiosity shuts down. Defenses go up.

The cleaner the correction, the harder people cling to the position. From the outside, this looks like stupidity. It usually isn’t.

It’s self-preservation.

Changing your mind is expensive.

It costs pride.

It costs status.

Sometimes it costs relationships.

Admitting you were wrong doesn’t update a belief. It rewrites a story. It forces you to revisit things you said, shared, defended — and sit with the possibility that you were wrong.

Most people would rather be wrong than embarrassed.

So bad arguments survive. Not because they’re persuasive, but because they’re safe. They keep you in good standing. They let you avoid that quiet, unwelcome realization — usually late at night — that you might have been played.

I’m not exempt. I’ve held losing positions far longer than I should have because exiting felt like admitting defeat. Doubling down feels like strength, even when it’s just damage with confidence.

Facts still matter.

Just not on the timeline we want, and not in environments where being wrong carries a social cost. Facts work when accepting them costs less than ignoring them.

Most public arguments fail for a simple reason.

They think they’re debating information.

They’re negotiating identity.

And until we’re honest about that, we’ll keep wondering why the facts were solid…

and the argument went nowhere.

Leave a comment